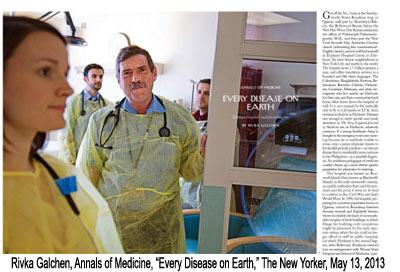

Get off the No. 7 train at the Seventy fourth Street-Broadway stop, in Queens, walk past La Abundancia Bakery, the Bollywood Beauty Salon, the New Hae Woon Dae Korean restaurant, the offices of Vishwanath Puttaswamygowda, M.D., and then past the New York Seventh-Day Adventist Chinese church (advertising free conversational-English classes), and you will find yourself at Elmhurst Hospital Center, in Elmhurst, the most diverse neighborhood in New York City and maybe in the world. The hospital serves 1.7 million patients a year, and offers translation services in a hundred and fifty-three languages. The Colombians, Bangladeshis, Koreans, Belarussians, Burmese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Croatians, Mexicans, and other immigrants who live nearby use Elmhurst for their care, and their communities back home often know about the hospital as well. It is not unusual for the exotically sick to fly to LaGuardia or J.F.K. from overseas to check in to Elmhurst. Diseases rare enough to merit special-case-study attention in The New England Journal of Medicine are, at Elmhurst, relatively common. If a young Southeast Asian is brought to the emergency room one morning because he is suddenly unable to move, even a junior physician knows to list familial periodic paralysis—an obscure disease that is considerably more common in the Philippines—as a possible diagnosis. An ambitious pedagogue of medicine couldn’t dream up a more diverse patient population for physicians-in-training.

Get off the No. 7 train at the Seventy fourth Street-Broadway stop, in Queens, walk past La Abundancia Bakery, the Bollywood Beauty Salon, the New Hae Woon Dae Korean restaurant, the offices of Vishwanath Puttaswamygowda, M.D., and then past the New York Seventh-Day Adventist Chinese church (advertising free conversational-English classes), and you will find yourself at Elmhurst Hospital Center, in Elmhurst, the most diverse neighborhood in New York City and maybe in the world. The hospital serves 1.7 million patients a year, and offers translation services in a hundred and fifty-three languages. The Colombians, Bangladeshis, Koreans, Belarussians, Burmese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Croatians, Mexicans, and other immigrants who live nearby use Elmhurst for their care, and their communities back home often know about the hospital as well. It is not unusual for the exotically sick to fly to LaGuardia or J.F.K. from overseas to check in to Elmhurst. Diseases rare enough to merit special-case-study attention in The New England Journal of Medicine are, at Elmhurst, relatively common. If a young Southeast Asian is brought to the emergency room one morning because he is suddenly unable to move, even a junior physician knows to list familial periodic paralysis—an obscure disease that is considerably more common in the Philippines—as a possible diagnosis. An ambitious pedagogue of medicine couldn’t dream up a more diverse patient population for physicians-in-training.

The hospital was started on Roosevelt Island (then known as Blackwell’s Island), in the early nineteenth century, as a public institution that cared for prisoners and the poor; it went on to tend to soldiers in the Civil War and both World Wars. In 1950, the hospital, preparing for a postwar population boom in Queens, moved to Broadway between Seventy-seventh and Eightieth Streets, where it inhabits the kind of unremarkable complex of brick buildings in which filings for building-code exceptions might be processed. In the early nineteen-sixties, when the city could no longer afford to staff its public hospitals (of which Elmhurst is the second largest, after Bellevue), Elmhurst entered into an arrangement with Mount Sinai Hospital and School of Medicine, a private institution on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Today, most physicians practicing at Elmhurst are interns, residents, and faculty professors at Mount Sinai. Elmhurst gets inexpensive staff; Sinai gets a unique training center. “It is pretty much universally residents’ favorite place to rotate,” Dr. David Muller, the dean for medical education at Mount Sinai, told me. If you want to learn not to be misled by the glittering chest X-ray of a Korean patient—in Korean acupuncture, the tips of the needles break off and remain lodged under the skin—go to Elmhurst.

Doctors also like to train at Elmhurst because of Dr. Joseph Lieber, a diagnostician and clinical educator who has been at Elmhurst, working from 4 A.M. until late at night, almost every day for the past twenty-five years. Practicing medicine at Elmhurst entails a daunting workload—at times, the hospital runs at a-hundred-and-forty-per-cent capacity—and the pay is not competitive with that of a private hospital or office. Yet an unusual number of doctors who train at Elmhurst choose to return to work there full time; they invariably cite Lieber as one of their main reasons for returning. His office is cluttered with tchotchkes from all over the world—a peaceful alpaca, a monkey in a toboggan, a miniature Taj Mahal—but, when I asked him about his travels, he said, “Maybe twice a month, I travel over to Sinai for teaching. Also, on Sundays, it’s true, I tend to go home earlier.”

Source: newyorker.com