Tags: Amber McGraw Walsh | Anna Timmerman | health system management | healthcare reform | McGuireWoods | Scott Becker

This article explores eight of the most challenging and interesting issues that hospitals are facing as they move into 2013. Such issues include physician alignment strategy, the ability of hospitals to stay independent, the development of accountable care organizations, the evolving priorities and concerns of CEOs and several other issues.

This article is written within the context of healthcare consolidation that is occurring at all levels. At the hospital level, hospitals are merging into other hospitals and independent hospitals are finding it more challenging to thrive on their own. At the hospital–physician level, the system has shifted toward one in which nearly 50 percent of all physicians are employed by hospitals and health systems, and nearly 80 percent of all physicians have some sort of financial relationship with hospitals. There is also increased consolidation among payors (although a great deal of this consolidation has already happened over the last 10 years). This has resulted in only several key payors existing in most markets. Finally, payors are increasingly re-entering the healthcare provider business, either as a hedge against provider market power in certain markets or in an effort to attempt investment in areas outside of insurance.

1. Physician alignment

The healthcare industry saw a wave of physician employment by hospitals back in the 1990s, and hospitals are again pursuing employment of physicians as a core strategy. Employing physicians tends to work in a fee-for-service environment and should also work as hospitals move forward into an ACO managed-care type of environment. The downside to a physician employment strategy is that it is expensive for the hospital, and there are increasing anecdotal discussions about the losses per physician that systems suffer as they employ physicians in larger numbers. Here, the average productivity of the employed physicians seems to be declining. Initially, as hospitals began to again employ physicians, there had been great focus on hiring the most productive physicians. Now it seems as though many hospitals have an “all in” strategy and have hired with less focus on the most productive physicians. Thus, the average productivity per physician has regressed to a more average level. This means the losses on professional fees are more significant, and it is harder to “make up the numbers” on the technical side. There are, of course, serious legal issues with attempting to make up the financial losses on the technical side.

a. Other physician financial relationships

Many systems, in contrast to a direct-employment strategy, focus on entering into co-management, joint ventures, call coverage, medical directorships and other financial relationships with physicians. Increasingly, hospitals are concerned about not having financial relationships with their admitting physicians. Many hospitals examine a top-25 admitter analysis or use a similar means to assess how dependent they are on their key physicians. Here, they examine whether or not key physicians are “free agents.”

b. Decreasing technical fees

It has been estimated that hospitals receive 5 to 10 times the technical fee revenues than the amount they invest on the professional employment salary side in certain physician specialties. (See Merritt Hawkins Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Salary 2010 report). For example, the average orthopedic surgeon may have a salary of $400,000 to $450,000 and generate $2,117,000 in revenues. However, as the physician employment boom has expanded, this number is likely becoming much lower on average.

c. Hospital-owned practices

Successful hospital-owned physician practices mix a pro-physician autonomous culture with great competency in the way that the practice handles its affairs. The hospital also must make sure that it pays physicians fairly. This does not mean that the hospital must be the highest-pay alternative for a physician.

d. Physician shortages

The financial sustainability of the employment model will play out over the next several years as hospitals face changes in revenues. However, for a variety of reasons, including the fact that there are likely to be significant physician shortages in many markets, doctors may retain significant market power in connection with their relationships with hospitals and other entities. This will be very market dependent. For example, according to Dr. G. Richard Olds, dean of the new medical school at the University of California, Riverside (a school that was founded in part to address the region’s physician shortage), “We have a shortage of every kind of doctor, except for plastic surgeons and dermatologists. . . . We’ll have a 5,000 physician shortage in 10 years, no matter what anybody does.” (“Doctor Shortage Likely to Worsen with Health Law,” Annie Lowry & Robert Pear, The New York Times, July 28, 2012; see also “Medical Schools Can’t Keep Up,” Suzanne Sataline & Shirley S. Wang, Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2012.)

e. Physician referrals/leakage

As reimbursement becomes tighter for many hospitals, we see many more health systems very closely examine what they refer to as “leakage.” In essence, they examine statistics to see how many cases from employed and affiliated physicians are going to other systems. This is a very substantial issue from a financial perspective but also involves significant legal questions as to what can and cannot be required of physicians in connection with referral patterns.

2. Sustainability of independent hospitals

Many hospitals are examining whether they will be able to survive as independent entities over the next several years. A couple of studies have looked at the key factors leading to hospital bankruptcies and the key factors that can be used to assess whether a hospital is in a position to survive independently or not. One study, for example, shows that the three biggest causes of financial instability for a hospital and potentially leading to bankruptcy are mismanagement, increased competition and significant reimbursement changes. For an overview of issues impacting hospital viability, see “Factors Associated with Hospital Bankruptcies: A Political and Economic Framework” by Amy Yarbrough Landry & Robert J. Landry published in the Journal of Healthcare Management in July/August 2009. The article also notes that “bankrupt hospitals are smaller than their competitors. They are also less likely to belong to a system and more likely to be investor owned.”

Another study by Kurt Salmon and Associates explained six factors which can be used to help assess whether or not a hospital can survive independently. These included:

Does it have geographic barriers?

What does its payor mix look like — is it positive or negative?

Does it have a substantial physician alignment strategy, or is it highly dependent on free agent physicians?

What does its asset base look like? Does it need to make significant capital investments? Does it need to make significant renovations or build a replacement hospital? Does it have other significant obligations ahead that it can’t fund?

What is its cost structure? Is it locked into long-term pension liabilities? Long-term lease rates? Or other long-term fixed costs that are not changeable?

Does it have a high standard quality of care? Alternatively, is it the type of hospital that a board member would not take his or her family to?

These are some of the core questions that one examines in trying to assess whether a hospital must look for a partner.

3. Accountable care organizations

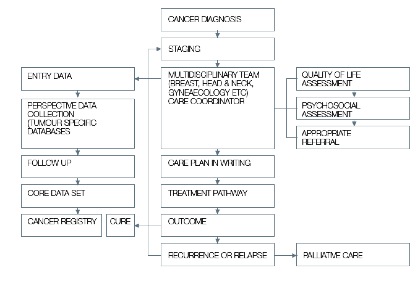

ACO formation is growing, but it is not yet clear how many beneficiaries ACOs will actually serve. The great majority of ACO development has come from hospitals, as opposed to physician groups or payors. According to a study by Leavitt Partners, 60 percent of ACOs are sponsored by hospitals, 23 percent are sponsored by physician groups, and 16 percent are sponsored by health plans (see graph below).

For graph, see “Can Accountable-Care Organizations Improve Health Care While Reducing Costs?,” Anna Wilde Mathews, Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2012.

Large physician groups can also be well-positioned to develop ACOs. ACOs, however, are very expensive to develop, with estimates of the real cost to develop them tending to be very high. Further, ACOs largely favor a tightly knit system where one can assure that patients are seen by physicians and providers at in-network rates, rather than out-of-panel and out-of-network rates. Thus, the development of shared savings agreements and ACOs is another institutional effort that favors the employed-physician model versus other models.

Some experts are skeptical however. Thought leaders, such as Tom Scully, partner at Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe, commented on ACOs as follows:

The biggest flaw with ACOs is that they are driving more power to hospitals — not to doctors. Very scary, and I am a hospital guy. The goal of ACOs was to organize doctors to focus more on patients and keep the patients out of hospitals. Instead, doctors are selling practices to hospitals in droves.

The start-up cost of a real ACO is probably $30 million and up in a midsize market — and doctors don’t have that capital. So hospitals are pitching that they will be ACOs, and buying up practices. Ever meet a hospital administrator who wants to work to empty his beds? This means more power in expensive institutions, more consolidation of those giants — and more bricks and mortar and more costs. And with zero antitrust enforcement in the last 30 years in the hospital world, we are cruising for regional hospital-based oligopolies — not good for doctors, patients or our hopes for a more efficient system. And the well-intentioned concept of ACOs is feeding that fire.

(“Can Accountable-Care Organizations Improve Health Care While Reducing Costs?,” Anna Wilde Mathews, Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2012.)

Similarly, Jeff Goldsmith, who is the president of Health Futures, Inc., has warned that:

Managed care is not merely a matter of large populations (5,000 to 20,000 patients probably isn’t large enough), but of subpopulations with unique health problems that require different protocols and approaches to improving their care. In the general population, the healthiest half account for a grand total of 3 percent of health costs. If those are the folks you end up worrying about in an ACO, you’re wasting your time. It is the incredibly heterogeneous 5 percent of the population that generates 47 percent of all costs that you need to focus on, and if you don’t have enough of them in your “attributed” population, you cannot concentrate the resources to change their care and lives.

(“Can Accountable-Care Organizations Improve Health Care While Reducing Costs?,” Anna Wilde Mathews, Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2012.)

4. Physician leadership burn out

The evolution of healthcare can require new roles for physicians, from each a clinical and management perspective. It is an open question as to whether the physician community is wholly interested and/or has the energy to take on new leadership roles. Many physician organizations suffer from a shortage of physicians willing to put in significant non-clinical time toward clinic leadership. The root of this unwillingness may be that more senior physicians are somewhat burned out, or it could be that younger physicians really want a “job” instead of to be a leader in their organization.

For example, one study by the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., found that “while the medical profession prepares for treating millions of patients who will be newly insured under the healthcare law . . . nearly 1 in 2 (45.8 percent) of the nation’s doctors already suffer a symptom of burnout. ‘The rates are higher than expected,’ says lead author and physician Tait Shanafelt. ‘We expected maybe 1 out of 3. Before healthcare reform takes hold, it’s a concern that those docs are already operating at the margins.'” (“Doctor Burnout: Nearly Half of Physicians Report Symptoms,” Janice Lloyd, USA Today, August 21, 2012.)

This burnout could have a very significant impact as:

Unhappy doctors [could] cut back their hours or retire early. In turn, that could further stress the overstretched medical system. For example, [one expert] says, it may exacerbate the country’s existing doctor shortage, predicted to grow to more than 60,000 within three years, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. The study ranked medical specialties by the percentage of doctors who are burned out — or conversely, satisfied with their jobs. Emergency doctors ranked lowest, with a burnout rate of 70 percent, while practitioners in such fields as dermatology and pediatrics were among the most content. Already, [another expert] says, prospective doctors have taken notice of older physicians in badly afflicted specialties like general surgery — which the study places last in career satisfaction — and are choosing not to enter them. “Our medical students are seeing general surgeons and primary care physicians burned out, and they don’t want any part,” he says.”

(“The Many Dangers Posed by Burned-Out Doctors, Chase Scheinbaum, Businessweek, August 22, 2012.)

5. Chief executive officer concerns; ACHE Study

An American College of Healthcare Executive survey recently analyzed the core concerns weighing on chief executive officers. The top concerns, in order, included financial challenges, healthcare reform, patient safety and quality and government mandates. (See chart below). It is particularly interesting to see the growth of concern focused on quality as compared to 5 or 10 years ago.

For more information regarding the ACHE study and a copy of this chart, see http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm.

Further, CEOs are concerned about labor costs, loss of procedures, less indemnity insurance, more uninsured patients and increased payor leverage. Other key factors the CEOs were concerned about in the ACHE study included Medicaid reimbursement, decreased government funding, Medicare reimbursement, bad debt and decreasing inpatient volumes. (See chart below).

For a copy of this chart, see http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm.

6. Orthopedics

In 2011, nearly 600,000 knee replacements were performed in the United States for a total cost of about $9 billion dollars. This statistic, while meaningless in itself, gives some sense of why so much effort is still placed on hospital alignment with orthopedic physicians and how important orthopedic dollars are to individual health and hospital systems. One article noted that “at about $15,000 each, the total annual tab for the operations performed on patients of any age is now about $9 billion.” (“Rise in Knee Replacements Boosts Federal Health Costs,” Shirley S. Wang, Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2012.)

7. Population health

Increasingly, parties talk about population health, or the improvement of an entire population’s health, as a potential answer and approach to healthcare. However, despite its potential benefits, it is hard to see how population health is likely to work in very fragmented, large communities because, in part, it may be difficult to coordinate such efforts and for systems to reap the benefits of investments in population health management. In contrast, where a hospital is the key provider in an area and there is a not lot of competition, it is easier to see the hospital system wholly engaging in population health.

8. Healthcare information technology

Healthcare information technology is an area of great interest and one which has seen a great disparity between the amount of money put in and the general lack of results to-date. One constantly hears the refrain of decreased productivity in physicians, particularly for the first few years after electronic medical records are installed, as well as concerns with up-coding through the use of electronic medical records and concerns that the national labor force is not well-positioned to actually service and handle the growth of electronic medical records technology. In addition, providers will increasingly be held hostage to one or two different systems that the major electronic medical records companies offer, which may not be a positive development.

For example:

Customers, such as New Hampshire’s Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center are feeling the pinch. DHMC which implemented Epic last year at a cost of $80 million, expects a weak operating performance in 2012, partly because of expenses related to Epic.

Now, re-read the definition of the Stockholm syndrome and see if it isn’t apt. But it doesn’t have to be this way, as [the author has] noted in quoting an article by Kenneth Mandl and Zak Kohane in the New England Journal of Medicine:

It is a widely accepted myth that medicine requires complex, highly specialized information-technology (IT) systems. This myth continues to justify soaring IT costs, burdensome physician workloads, and stagnation in innovation — while doctors become increasingly bound to documentation and communication products that are functionally decades behind those they use in their “civilian” life.

We believe that EHR vendors propagate the myth that health IT is qualitatively different from industrial and consumer products in order to protect their prices and market share and block new entrants. In reality, diverse functionality needn’t reside within single EHR systems, and there’s a clear path toward better, safer, cheaper, and nimbler tools for managing health care’s complex tasks.

(“The Stockholm Syndrome and EMRs, Paul Levy, Not Running a Hospital Blog, October 17, 2012, available at http://runningahospital.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-stockholm-syndrome-and-emrs.html.)

The burden that electronic medical records imposes can be significant. In the opinion of one physician, “Tasks that once took seconds to perform on paper now require multistepped points and clicks through a maze of menus. Checking patients into the office is an odyssey involving scanners and the collection of demographic data – their race, their preferred language, and so much more – required by Medicare to prove that we are achieving ‘meaningful use’ of our EMR. What ‘meaningful use’ means no one knows for sure, but our manual on how to achieve it is 150 pages long.” (“Physician, Steel Thyself for Electronic Records,” Anne Marie Valinoti, Wall Street Journal, October 22, 2012.)

Sumber: beckershospitalreview.com